Q&A with Carole Wagener, Author of "The Hardest Year: A Love Story in Letters During the Vietnam War"

Originally from a small town in northern Wisconsin, Carole Wagener retired from a career in physical therapy in 2018 and concentrated her efforts on a writing career that was already underway. She’s a charter member of Coastal Dunes California Writers Club and has published short stories and poetry in that group’s anthologies. Carole recently self-published her first book, The Hardest Year: A Love Story in Letters During the Vietnam War. Her husband, William, who wrote roughly half of the letters in the book, shares author credit.

I got to know Carole first as an editing client (I did a developmental edit on an early version of The Hardest Year), and then as a student in my life story writing classes. It has been a gratifying experience to witness her book evolve from an early draft to a polished work. During our Zoom interview, I focused on questions about the writing and self-publishing process so other memoirists may learn from the decisions she made along the way.

QUESTION: Could you please start by talking about when and why you set out to write this book?

CAROLE WAGENER: I've been a member of the Coastal Dunes California Writers Club for the last seven years, and one of the speakers who came to talk to us in 2016 wrote a book called Aldous Huxley's Hands. She had gotten ahold of some of Aldous Huxley’s letters through his daughter, and I think he had some kind of correspondence with her father and other notable people. When I came home that day after her talk, my husband came out of the garage carrying a shoebox of letters from Vietnam. The same day! I said, “Give me those. I think I could write a book using those letters.”

And I set out to do that. I was hoping I could get the letters to tell the story. I typed them up in sequence and had my friend read them, but she said, “I hate to tell you, but it's boring.”

Around the same time, I went to the Central Coast Writers Conference. You were there. I think you were on a panel, right? You had some cards, so I took one home with me. And then a friend who was helping me organize my material said I needed to hire a developmental editor. I had your card, and when I found out you were from Wisconsin, too, you were a shoo-in.

When Bill surfaced with those letters, what were you writing at that point?

I started writing stories about my grandparents and my parents. And then I wrote some poetry for my sisters. My goal was to write a little something for everybody in the family. And then, because the writers group was publishing their own anthologies, that's how I got started getting published. With the anthologies, one year was nonfiction and then the following year was fiction. I got pretty good at nonfiction. With memoir, you're working off your memories and maybe some photographs, and for some reason, I have a memory like an elephant. I can remember all the details: what it felt like standing in the driveway waiting for my dad with my little kerchief on when I was five years old. And it seems the more you write, the more the memories come back to you—peeling the layers off the onion. So, I wrote fiction, but memoir was more my niche.

If you had known that day when Bill came in from the garage with the letters that it was going to take you seven years to write a book, do you think you would have decided to do it?

I’d gone to another lecture at a bookstore that I really enjoyed going to when I was visiting my daughter in Melbourne, Australia. This lady spoke about writing a book, and she said it took her five years, because she was working—and I was also working at this time. And so, I figured five years, that's a long time, but that might be what it takes. At the five year mark, I was ready to quit. I didn't want to write anymore. I didn't want to try to get into my emotions anymore. I just wanted to quit. One of the members of the writers club, Judy, is also my editor, and she told me [at five years], “The book’s not ready to publish.” She had been in on it as long as you had been in. She was my reader, she was giving me suggestions, maybe writing some sentences for me and giving me writing prompts for the fiction I was working on. So, that was instrumental. After she told me that, I just accepted that I had to finish this however long it took. I got over being all antsy about it because it wasn't ready, and she was right. I just kind of relaxed and went with the flow and kept writing and editing. You know how long and tedious the editing is.

I do know. But I've been doing it for a long time. Writing isn't your first profession. I've been impressed by your stamina for the project. I'm wondering what kind of advice you have for people who would like to follow in your footsteps, first-time book authors who feel themselves overwhelmed by how long it can take.

When the timing is right, just let it happen. One time I was stuck. I was literally stuck, right before I met you. I remember at the Central Coast Writers Conference, they had these fifteen-minute breakouts where you can sign up with another author or an agent. And so, I signed up with two agents, and that was not very encouraging. But I also signed up with Peter Dunne, a writer in Hollywood. He wrote for Eight is Enough and Dr. Quinn: Medicine Woman, and everyone had told me how nice he was—it can be intimidating when you talk to someone that's been in the business. I was allowed to give him three to five pages of my writing, and he was encouraging. The second year I went to the conference, I was paired up with him again. After he read how I had changed the opening of my book from the year before, he said, “Your story is going to be fantastic.” That gave me a lot of encouragement.

The other thing Peter Dunne told me—and I was really struggling—is that a story can have two protagonists, or maybe even three. And I didn't realize that the war or something else going on in the culture could be an antagonist. I thought my husband was the antagonist! He does antagonize me at times in the story, but I didn't want to make him the bad guy. So, when Peter told me that, it was very freeing, because now I had more focus and direction. I knew where I was going.

At the end of the conference, they asked us, “Are you going to go home and write tonight?” I mean, it was like nine o'clock, and I had to drive an hour to get home! Well, lo and behold, I was hungry, so I stopped at McDonald's halfway home. And as I was driving through the drive-through to get my hamburger, this muse or something just came over me, and I wanted to write. So, I parked in the parking lot and got out my pen and paper, and I wrote like three paragraphs about how I was angry about the war, letting my anger out about Vietnam and how it affected and changed our lives. That was a big turning point for me. Before that, I almost had writer's block. I could have just quit and said I don't know how to do this. But once he helped me with that, that really added some light to my imagination. The light bulb went on. Then I needed to figure out how to organize everything, which is when I met you.

A photo of the author taken by her daughter at Grover Beach, California

“I didn’t realize that the war or something else going on in the culture could be an antagonist. ”

A lot of people, after they’ve received a developmental edit of a manuscript, feel defeated and even take it personally. It can be difficult to receive constructive criticism on something you’ve worked on for so long. You worked with several editors, and I'm curious whether you ever had that kind of reaction.

Yeah, you can't have your feelings hurt, but I did have my feelings hurt one time. Someone sponsored a day-long seminar, and I had brought the first three or five pages of my book along. Well, the man sitting next to me was a beta reader. Now, a beta reader is someone who reads over your work, but after he read over my work, he cut it down to just three paragraphs. And I thought, Oh, he's like a beta fish, chewing it up—like two beta fish fighting. That was rather discouraging. I’m sure his suggestions were good—I saved everything he told me and went home and rewrote it—but I also decided I would only work with females after that. The book is written from a female point of view.

You share author credit with your husband, whose letters from Vietnam form the backbone of the story. Was he always behind the idea of turning this into a book?

I did most of the writing, and I put all the letters together. He wrote one chapter—I couldn't write about his homecoming because I wasn't there. I don't think he could have written the book on his own because he has PTSD and fifty percent disability from that time. He didn't even read the entire book until it was in print. Then he couldn't put it down. But now, when he's listening to the audio, it becomes even more real for him. Last night, when we were listening to the chapter where he left for Vietnam and I kept waving to him from the tarmac, he started crying. He was trying to be strong at the time, but I'm sure he was scared too; he probably didn't want to leave. I think there's healing in writing, and I think it's good that he can cry now. He couldn't cry back then, but it’s like the book gives him permission to cry now and get those emotions out. Those memories are deep, they're really very deep.

Did you have any creative differences in the process? Did you have to make compromises?

Well, when you're writing and collaborating, one person gets to make the final decisions. That was me. For example, he didn't want me to put down the story where he went out and rescued the convoy. For some reason, he didn't want that story in there. Maybe because he got court martialed, or maybe it's too painful to relive it, but I had to have that story. I said, “That's the climax. That's the most important story. I have to put that in there. If you want me to omit some details, I can do that.”

Also, if he had written the book without me, he would have made it too political. He wrote an afterword that I left out. It was too political—you don’t want to turn off your reader.

There's politics in war, and you don't hide the opinions you had at the time, and your conclusion is also kind of political, but I don't read this book and feel like you're trying to convince the reader of something. It doesn't strike me as an ideological book.

Well, I did include the election where Richard Nixon was elected over Hubert Humphrey, and Bill had his opinions about Hubert Humphrey. “Get his ass over here!” But that was what was going on in the political world. That was very important. And the reason I supported Nixon is I thought he was going to bring the troops home early. Of course, I was all of twenty years old.

Going back to the question, I liked including the epilogue, because now I’m relating Vietnam to the war in Iraq. These are my conclusions thirty years later, and I added how I got here, my history of joining the Libertarian Party [for a time] and learning more about how our government works and trying to educate people. I’m saying, this is my conclusion after having lived through it, and so you might want to think about it.

You belong to a couple of writers groups, including the life story writing class we’re in together, and you worked with a batch of editors. Thinking about authors who are looking to publish a memoir like you’ve done, which of all the sources and tools you pulled from do you think was the most useful or most worth your money or your time?

Biting the bullet and hiring [a developmental editor], and then I hired Eldonna Edwards, who does line-by-line editing. I was a little bit concerned that my voice was going to be lost in the process, but Eldonna told me, “Now, I'm just going to be whispering in your ear. Carole.” Sometimes it was just changing where I put the sentence or the paragraph. In one of the last chapters where I was riding on the bus, and a protester steps out in front of the bus, and the bus stops—at that point in the story, she reorganized what I had written. I had written my story chronologically . . . she broke it apart to make it much more exciting. I was really impressed with what she did.

And then I had a copyeditor. There were four editors who had their hands on that thing.

So, biting the bullet and hiring editors was worth it in the end, you think?

Yes, because now I had something that was publishable. Otherwise, it might have just been for family and friends. I did try to get it out to a couple of publishing houses, but then Covid hit, and it was like the smaller ones weren't even opening submissions, and the bigger ones I didn't hear back from. You have to know your market. This memoir is geared toward veterans and their families; the general public, too, but mostly veterans. At one point I decided to try two small publishers that have already published other people's [military-oriented] books, but they weren't opening submissions. One told me to get an agent, but I was not interested in getting an agent, for it to drag out for a couple more years, so that’s when I decided to self-publish. My husband and I put January 1, 2023, as our deadline: if we hadn't heard from anyone, we were going to hire Brian Schwartz at SelfPublish.org.

Can you talk a little bit about the pros and cons of self-publishing? One of the pros you just alluded to is that your book is out in the world now and you don't have to wait two years, which you would likely be doing if you had found a publisher, either through an agent or on your own. Are there other pros and cons you can think of regarding self-publishing?

One of the pros is that I have total control of what's in the book. I had the final decision on the cover design. Brian and I finished the formatting together, and that was nice to work with somebody professional, because I wouldn't even know how to get this thing up on Kindle. I'm not that computer savvy.

The con is I had to pay for all this. I thought maybe we could get it done in ten hours, but now it's taken twenty hours because there's a lot of detail, and an hour goes by fast when you're talking to someone. Though, we only talked once; most of it has been done over the internet.

I want to give an example. An author came to our writers club to speak about his book. He's also a Vietnam veteran. He flew combat missions from Thailand. He sold his book to Penguin, and they put a cover on he did not like, and they took a whole chapter out that he thought was very important to the book. He was not happy with it. They only sold 5,000 copies. So, he got the rights back; Brian [at selfpublish.org] helped him redo the cover; he put that chapter back in; and he sold 27,000 copies on his own. This was a number of years ago, and I still see him at author events and things. He's still promoting the book, and he's written three or four others.

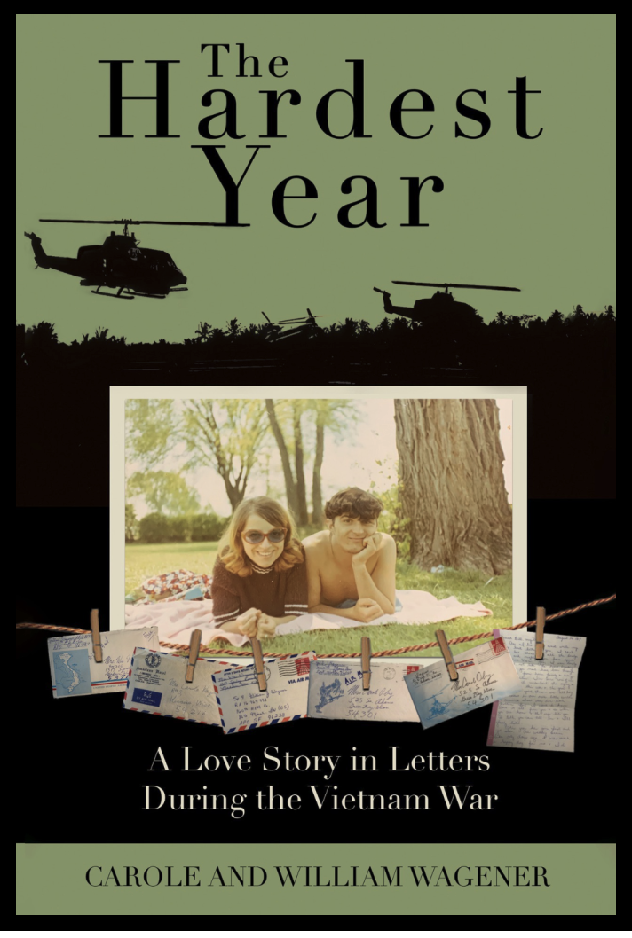

I learned from that example that Vietnam books are selling. And I'm very happy with my cover design. My daughter and I had basically done the cover, and then the cover designer [through SelfPublish.org] just put the letters on the little clothesline and added the helicopters. That didn't cost much money.

When you worked with Brian at SelfPublish.org, was it all money upfront, or does he get a portion of your proceeds as the book sells?

He does not get any portion of the proceeds. It's all upfront. You could hire him by the hour, but it's cheaper to get a block of ten hours. A simple book that you just want to put up on Kindle could get done in less than ten hours. But [ours was more involved]: we have the Kindle that came out first, then a paperback that came out second, and the audiobook will be third.

Brian connected me with two readers from Atlanta, Georgia, who are both actors. They're married. We had to go through something called ACX. They have a list of narrators, so I could have had several people narrate it, but I wanted both male and female voices because the book really lends itself to that. So, they gave me a demo of about six minutes, and it was really good. They had an opening right then, so I said, “I'll take that, right now. I don't want to wait three months!”

That was the good part: Brian already knew all these people. He had them all in place. And he referred me to a copyeditor. The copyediting wasn’t too expensive. Let’s see, we started in January, and the Kindle came out in April, the paperback came out in May, and the audio will come out in June. So, we got it all done in six months, which I think is pretty amazing. Pretty quick.

The way the audio works is I'm going to share the profit with the readers. Audiobooks is owned by Amazon, so they take sixty percent of the proceeds the first seven years, and then I'm splitting the forty percent with the narrators—they take twenty and I take twenty. Audiobooks seem to be the highest retail price of all the books, and they’re selling.

Carole and William Wagener at their wedding

Your paperback costs almost twenty dollars on Amazon.

I don't know what the audio will be yet. I guess ACX will set the price. The Kindle is about seven dollars now, and I get to keep somewhere around seventy percent of that.

Can you talk a little bit about the photos you included in the book? Does that cost extra, and how did you make decisions about how many to include?

I talked to other authors. I knew I could have about thirty pictures. I chose some that were already black-and-white, and some were in color, because during the 1960s we were just kind of transitioning to color prints. Some of them my husband developed in the photo lab on base—they had a lab and a swimming pool on base. He had taken photography in high school, so as long as they had the chemicals and the power was on, he could go and develop his own black-and-white film. Interestingly, on Kindle, the color ones will be in color because it doesn't cost any ink. It would cost more if you were going to print color pictures because you have to have glossy paper and the color ink.

We thought about printing some original letters and newspaper clippings, but Brian said they wouldn’t come out well, it would make the book look cheap.

It sounds like that's another benefit of working with somebody like Brian: he has experience with what's going to look good and what's not going to look good. When you said you knew you could have about thirty photos, what was that based on, the ultimate price you wanted the book to cost the reader, or the size of the book?

More the size of the book. This book has around 300 pages, and if it got too much bigger, I maybe would have had to cut some photos. It has to do with this seam here [points to the book’s binding]. Get too many pages in there and it's not going to hold, the book is going to fall apart. I've had other self-published books where pages actually were coming out. Maybe the seam was too small, I don't know.

Another decision we made was, I had footnotes on every page, and we decided to make them endnotes in the back of the book.

I saw that. Why did you decide to do it that way?

It was easier to format, and also, it doesn’t interrupt the reader. The reader can keep going and look up the footnotes if they want. It just seemed logistically a lot easier to set up; plus, it gives you something to look at at the end. And then, a friend suggested we do the glossary with all the military terms. She also suggested the map [of South Vietnam at the front of the book]. We had to hire somebody to do a line drawing of the map.

Could you talk about how you dealt with the letters? Did you change any parts of the letters? Did you take paragraphs out in order to move the story along? What kinds of decisions did you make with the letters?

It took me about a year to organize all the letters because I had to read them through; I had to organize them chronologically by month, and my husband's [mailed through the military from Vietnam] didn't have any postmark on them, so I had to open them and check the dates. And then, one of my friends who beta read it asked, “Didn't you have any letters from his relatives? You really should include some of the family letters.” So, I went to that box, and I peeled out a couple letters from his parents and my parents.

I cut out a lot of the letters because of repetition. How many times can I say “I love you,” you know? I was trying to make the story flow using the letters, and also by using some dialogue and emotion. I tried to get into the point of view of a twenty-year-old, and even though I had a hard time getting in touch with my emotions at that age— I was kind of stuffing everything down back then—I just had to work it through and rework it to try to get it all to make sense.

But you ran the letters mostly verbatim?

Yes. Even if I took select paragraphs out, I didn’t change anything else. I think I added one line where my editor thought I needed to. I had a real problem using the f-word. As we got through the year, the f-word was coming up in the letters more often. I really struggled with whether to include it. I decided that because he was in the military, it was appropriate for him to use the f-word, but because I was a nice little girl and we didn’t use the f-word at the time—we were raised in the church, and we weren’t allowed to be potty-mouthed—Carole doesn’t use the f-word, but Bill does. It’s in his letters . . . because that’s the way they talked in the military.

So, you’re saying that Carole in the letters didn’t use the f-word, and you made that consistent with Carole the character outside the letters?

Yes. Back then, we might say “shoot” instead of s-h-i-t, but girls did not say the f-word at all in the late 1960s. If you did, your parents would be really upset with you.

Where did you get your blurbs? Is that the purpose of getting beta readers?

Yes. I got this blurb on the back cover from Tom Avitabile because he did the beta read. I paid him to do the beta read, so I got my money’s worth. And then I met other authors through Wisconsin Alumni magazine [officially called On Wisconsin]. They always do reviews of some of the new books that come out, so I met two authors from Wisconsin who had written military books. I sent them my manuscript, they read it early, and they gave me two good blurbs. Then, with the writers club, we exchange beta reading. The people in our life story writing class, they were beta listeners; they heard the whole book, and that was very helpful because now I have another fifteen or twenty people giving me input, like with the story’s flow, and helping me if I couldn’t find a word. I was constantly editing.

Andrew Wiest, from my quotation [or epigraph] page, is a professor at the University of Southern Mississippi. He has also done documentaries, and he wrote a book about the wives of Vietnam veterans. That was the only comp I could find, of a book that was close to [comparable with] mine, so I decided one day I was going to give him a call. I looked him up and got his work phone number and left a message, and thirty minutes later he called me back.

What are your plans for promotion?

I have an interview on Memorial Day with the Veterans Breakfast Club. There are usually about sixty veterans. I want to get word out to the veterans because then we can network by word-of-mouth. Then, I’m going to send the book to the Military Writers Society of America. They will judge it based on itself, and I could get a golden, silver, or bronze medallion to put on the cover. We’re going to do a launch on Amazon, probably in June: we’re going to give the e-book away for five days, to upload it for free. The idea is you want to get reviews. Right now, I have about six reviews. Brian says if you have about one hundred, the book will sell itself.

Good luck with that, Carole, and thank you so much for your time and advice for aspiring authors.

Some resources Carole passed along for other writers, and in particular other military and veteran writers:

· The Military Writers Society of America (MWSA) offers free writing classes to members. You don't have to be a veteran to join. Carole is currently at work turningThe Hardest Year into a screenplay; she took a screenwriting class through MWSA and learned a lot from the teacher, Edward Pomerantz, who has an impressive writing résumé. Carole is currently reading and recommends the book Save the Cat: The Last Book on Screenwriting That You'll Ever Need, by Blake Snyder.

· The Veterans Breakfast Club is run by Todd DePastino, who has a Zoom happy hour session every Monday. He often speaks with veterans who have written books. The club publishes a magazine and a blog. This group, says Carole, “really focuses on healing and camaraderie for the vets. They sponsor trips back to Vietnam for veterans. It's also good for people who like military history.”

· Writers local to the Central Coast of California may like to check out the Coastal Dunes Branch of the California Writers Club: coastaldunescwc.com. Carole is currently the club’s secretary.

· To learn more about Carole, visit carolewagener.com.